Fed Set to Raise Rates by 0.75 Point and Debate Size of Future Hikes.

Some officials are signaling greater unease with big rate rises to fight inflation

https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-set-to-raise-rates-by-0-75-point-and-debate-size-of-future-hikes-11666356757?mod=hp_major_pos1#cxrecs_s

By Nick Timiraos

Updated Oct. 21, 2022 4:57 pm ET

Federal Reserve officials are barreling toward another interest-rate rise of 0.75 percentage point at their meeting Nov. 1-2 and are likely to debate then whether and how to signal plans to approve a smaller increase in December.

“We will have a very thoughtful discussion about the pace of tightening at our next meeting,” Fed governor Christopher Waller said in a speech earlier this month.

Some officials have begun signaling their desire both to slow down the pace of increases soon and to stop raising rates early next year to see how their moves this year are slowing the economy. They want to reduce the risk of causing an unnecessarily sharp slowdown. Others have said it is too soon for those discussions because high inflation is proving to be more persistent and broad.

The S&P 500 closed up 2.4% on Friday, with all 11 sectors posting gains. The 10-year Treasury yield fell to 4.212% on Friday, from 4.225% on Thursday. Still, yields on the benchmark note rose 0.207 percentage point on the week, marking the 12th consecutive weekly gain.

The Fed has raised its benchmark federal-funds rate by 0.75 point at each of its past three meetings, most recently in September, bringing the rate to a range between 3% and 3.25%. Officials are raising rates at the most aggressive pace since the early 1980s. Until June, they hadn’t raised rates by 0.75 point since 1994.

Fed officials want higher borrowing costs and lower asset prices to slow economic activity by curbing spending, hiring and investment. They expect that to reduce demand and lower inflation over time.

Fed policy makers face a series of decisions. First, do they raise rates by a smaller half-point increment in December? And if so, how do they explain to the public that they aren’t backing down in their fight to prevent inflation from becoming entrenched?

Markets rallied in July and August on expectations that the Fed might slow rate rises. That conflicted with the central bank’s goals because easier financial conditions stimulate spending and economic growth. The rally prompted Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to redraft a major speech in late August to disabuse investors of any misperceptions about his inflation-fighting commitment.

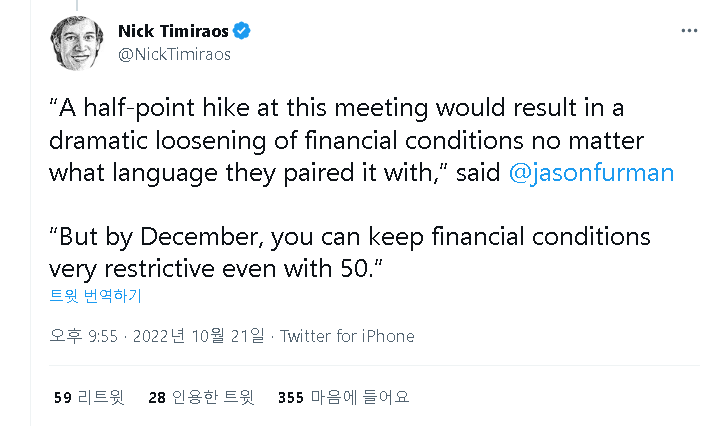

If officials are entertaining a half-point rate rise in December, they would want to prepare investors for that decision in the weeks after their Nov. 1-2 meeting without prompting another sustained rally.

“The time is now to start planning for stepping down,” said San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly during a talk at the University of California, Berkeley on Friday.

One possible solution would be for Fed officials to approve a half-point increase in December, while using their new economic projections to show they might lift rates somewhat higher in 2023 than they projected last month.

The Fed’s policies work through financial markets. Changes to the anticipated trajectory of rates—and not just what the Fed does at any meeting—can influence broader financial conditions.

Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester has signaled she would favor rate rises of 0.75 point at each of the Fed’s next two meetings because there hasn’t been progress on inflation. “We can’t let wishful thinking drive our policy decisions,” she said on Oct. 6.

Some officials have said they want to see proof that inflation is falling before easing up on rate increases. “Given our frankly disappointing lack of progress on curtailing inflation, I expect we will be well above 4% by the end of the year,” said Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker in remarks Thursday in Vineland, N.J.

Meanwhile, Fed Vice Chairwoman Lael Brainard and some other officials have recently hinted at unease with raising rates by 0.75 point beyond next month’s meeting. In a speech on Oct. 10, Ms. Brainard laid out a case for pausing rate rises at some point, noting how they influence the economy over time.

Other colleagues are concerned about the danger of raising rates too high. Chicago Fed President Charles Evans told reporters on Oct. 10 he was worried about assumptions that the Fed could just cut rates if it decided they were too high. Promptly lowering rates is always easier in theory than in practice, he said.

Mr. Evans said he would prefer to find a rate level that restricted economic growth enough to lower inflation and hold it there even if the Fed faced “a few not-so-great reports” on inflation.

“I worry that if the way you judge it is, ‘Oh, another bad inflation report—it must be that we need more [rate hikes],’… that puts us at somewhat greater risk of responding overly aggressive,” he said.

Kansas City Fed President Esther George also last week said she favored moving “steadier and slower” on rate increases. “A series of very super-sized rate increases might cause you to oversteer and not be able to see those turning points,” she said in a webinar on Oct. 14.

The ultimate result is likely to come down to what Mr. Powell decides as he seeks to fashion a consensus.

Officials will have two more months of several widely watched economic indicators before their meeting in mid-December, including on hiring and inflation. They pay close attention to a detailed measure of worker compensation called the employment-cost index, and the Labor Department report covering the July-to-September quarter is set for release on Oct. 28.

One challenge is that some of the strongest support for slowing down increases comes from so-called policy doves, who have traditionally favored easier monetary policy. Last year, those officials argued most forcefully for waiting to remove stimulus policies. Now, with inflation running near a four-decade high, it could be harder for their arguments to gain traction, said Neil Dutta, an economist at research firm Renaissance Macro.

“At critical junctures in the monetary-policy decision-making process, they’ve been spectacularly wrong,” said Mr. Dutta. “The doves are in the penalty box. There are costs to being wrong at key turning points over the last 18 to 24 months.”

Another concern is that inflation pressures have broadened despite some signs of potential relief. Commodity prices have fallen this summer. Easing supply-chain bottlenecks could lead to deceleration in goods prices, and the housing market is entering a deep slump.

But a strong labor market could lead to persistent wage growth that boosts prices in the labor-intensive services sector. That could keep prices rising on everything from haircuts to car repairs to veterinarian visits.

“The problem for me with trying to say, ‘Hey, it’s time to pause,’ is we’re not even sure that we’ve got rates high enough to push services inflation down,” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said Tuesday.

Investors in interest-rate futures markets now expect the Fed to raise rates to 5% by the spring, according to CME Group. Last month, most officials projected lifting rates to at least 4.6% next year.

If officials decide to raise rates by 0.5 point, or 50 basis points, in December, they would have reason to worry about triggering another market rally, said Kathy Bostjancic, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics. “The equity market has been so eager to see pivots by the Fed,” she said. “Fed officials have to explain that 50 basis points is still a meaningful increase.”

Investors are anticipating a sequence of pivots, from a slowdown in rate rises to a stop in rate rises to rate cuts. “They keep jumping ahead to the last pivot, and we’re a long way from the Fed cutting rates,” said Ms. Bostjancic.

The July rally reversed part of an earlier run-up in mortgage rates, which in turn supported a rebound in the housing market. If another market rally erupted this fall, the Fed might have to raise rates more than anticipated to slow down the economy, said Jason Furman, a Harvard University economist who served as a top adviser to former President Obama.

“The last thing you want is…to raise rates even more to undo all that,” said Mr. Furman.

Write to Nick Timiraos at nick.timiraos@wsj.com

https://twitter.com/NickTimiraos/status/1583441374988619777

'뉴스 - 미국·캐나다' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 美 금리인상 예상 (0) | 2022.11.01 |

|---|---|

| PCE 예상 상회했지만 임금상승률 낮아져…연준에 숨통 (0) | 2022.10.30 |

| 시장 단기 향방 열쇠는 '美 9월 고용보고서'가 쥐고 있다 (0) | 2022.10.05 |

| 마이크론 ‘어닝 쇼크’ 우려… 삼성·SK하이닉스 ‘3분기 빨간불’[출처] - (0) | 2022.09.26 |

| 폴 크루그먼 "인플레 둔화 시작"…스티븐 로치 "내년은 침체의 해" (0) | 2022.09.21 |